Just Another Prayer Group, or Something Else? ( Part II )

"Prayer. Isn't that what religious people do?"

First, before moving on to prayer, let's put some numbers on all those "religious people."

Just how big a group is that?

And of course, a key fact is that this is not one group. It is subdivided into sub-groups. And these do not always get along. If you doubt that lack of cooperation and compassion: Google "Crusades," or "Inquisition," or "Jansenism vs Jesuits," or "what was the war in Ireland about?," or almost anything under "current world events." Not much time? Just click here on Religious Persecution. For better or often worse, a link was often found in history between prayer or those who pray, and persecution.

Prayer, true prayer, is never persecution would say many.

Here are the numbers

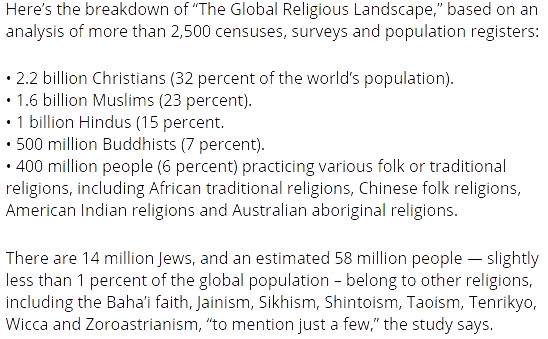

These were put together in 2012 by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, for 203 countries and territories, and summarized in a Washington Times article :

Answer Is? :

84% of the world's population subscribes to a religious faith of some form.

I have difficulty in passing over the above numbers without reflecting quietly a moment on 60 million Jewish lives destroyed in the Holocaust.

Do all these religious believers pray every day?

A very safe answer is : No.

How could that be? How do you know? Trust me. Ask around. So if being a believer does not always mean practicing prayer ...

Where can one find the experts in prayer? People who pray every day, and who's lives are formed by prayer ... and why do we think we want to find them?

We want to find them to better appreciate why to pray, or the benefits of prayer.

How to pray, when to pray, where to pray, who should pray, and to whom one should pray: these are components of prayer that risk getting one into lengthy answers with high rates of variability as we travel the world. Even if one moves around a large metropolis, answers will vary. An understandable variance, and as a function of who opens the door when we knock with our list of questions. This does not mean that we should be intolerant of differing answers. Quite the contrary. But let's move on.

Where are the experts?

Both lay persons, and those who have taken vows to participate with a religious order and do, could be our teachers. For me very quickly, the term monastics comes to mind.

What's special about "monastics"?

In general, they have made a lifelong commitment to prayer.

Some visible and less visible components of this commitment might be:

- Their primary commitment and life occupation is to prayer and a prayerful life.

- Prayer takes up a signficant portion of each day and sometimes night.

- To serve and accomplish this commitment, they have found over centuries, that it is easier to establish and maintain this full practice, if they withdraw from the non-monastic world.

- Viewed monastically, this is less a coming out of, and more a moving into.

- This withdrawal might be into physical monasteries living as communities of monastics, or alone in solitary enclosures, or simply at their "house" which is structured nevertheless, set up or even remodelled to support prayer, and to place distance between them and the "outside" world.

- Contact with the "outside world" may still take place in some monastic or prayerful practices. This may also occupy several hours each day, and might be for any of several purposes: teaching, social work, begging food (depending on the practice), participating in lay religious services, caring for the sick and injured, helping the poor, selling religious items, foods, beverages, crafts, paints and commodities to the public, and other means of support for their monastic community.

- A balance is frequently sought by those who direct monastic communities, in finding a workable and productive level of contact and communication between "inside" and "outside" worlds.

- In some communities there is no contact with the outside world. This a necessity supporting the intentions of such a community's monastics.

- Monastics do not pray into the void. They are praying to a named entity or source of energy that they believe in. The names for this entity vary from one religion to another, and one might even be praying to one's self. But usually, an "outside" direction for prayer is observed, usually linked to an "inside" self, and to which it should be closely tied. Establishing and maintaining this close tie is to be desired, encouraged, taught.

- The recipient of the monastic's prayer is invariably couched in a loving relationship. Celibate lives, and related issues, have their origin in not being polygamous with one's monastic love. Meaning, love is directed towards and developed with the recipient of the monastic's prayer. To take on a second loving relationship, well carried out, risks dividing the monastic's vow and commitment to prayer. Not all monastics are celibate.

- The monastic's self might be perceived as a part of a larger whole, such as "the universe" or a unifying collection of souls, energy, guiding spirits, or not.

- Often, to be distinguished from surrounding worldly society, a special dress or uniform is adopted.

- Physical items frequently become symbols in and of the monastic life.

- For centuries, monastics have learned, practiced and perfected various art forms and media. From calligraphy to music, painting, sculpture, gardening, plant medicine, culinary preparation, writing and archiving records: each becomes a prayer.

- Monastic prayer has a strong component of self discovery.

- Monastic prayer is very frequently directed towards problems in the outside world, and announced within the monastic community. These become prayer intentions.

- Monastic prayer takes on many forms. From quiet communion with a named entity which is their source of energy, to reading and prayer (Lectio Divina is one example), to active prayer, to sung prayer, to meditation, to praying through music or drama or ritual, to contemplative or centering prayer, to praying in one's very existence and actions.

- Names for the source of energy and target of prayer for the monastic vary according to religious tradition. God, Yahweh, Allah, etc. Buddha is revered but not worshipped as a god. Most practices are monitheistic, though prayers to saints, and holy ones are also prayer. In Buddhist tradition a bodhisattva is someone who has taken vows to save all living beings before saving him or herself. This is more in line with a Western tradition monastic's purpose. A Buddhist saint refers to someone who has actually reached "liberation," but can still be prayed to.

- The beliefs of the monastic are usually similar to other monastics in the same tradition. These beliefs are frequently codified by the religion to which the monastic belongs. One can nevertheless find some variation within the monastic community in what is personally emphasized as belief by the monastic. In some situations, there is little or no variation in beliefs, which are clearly transmitted, maintained, protected and vehemently defended. At times such defense simply takes the form of silence.

- Monastic communities have leaders, unless the monastic has styled his practice as a hermit. Even then, direction for the monastic in his or her prayer practice, if not provided from superiors in daily contact, may be found in readings from those who have lived the monastic life, and maintained its commitment, faced with all obstacles, and including the effect of living the monastic life itself.

- There is most frequently a "guide book" for the monastic. A principle source of guidance, such as Bibles, prayer rolls, or equivalent, and lesser but still important "guide books" such as a Psalter for instructions in praying and singing specific prayers.

- Monastics who have studied and learned their prayer practice well, almost invariably become teachers. First, of their learned prayer practice, and perhaps after, of other subjects. This contact with seekers on the path, including themselves as inner seekers, and the transformation into teachers and spiritual healers, if well realized, invariably brings with it a guiding principle: Compassion and its mirror image, Self-Compassion. Through prayer, succesful monastics learn how to send this Compassion into the world through their prayer and their practice.

- The monastic spirit and way of life includes bringing with one in all moments, especially during forays or work into the "outside" world, a spirit of prayerfulness. Events encountered in the "outside" world must become occasions for, and inspire, prayer. Any activity is to be performed in a manner that it too, is prayer.

- And finally here, the monastic, in most traditions, if seeking something, some objective, some end point,... that thing when named would almost assuredly be Peace. Monastics are Peace experts. Monastics are Peace seekers. Monastics are lovers of Peace.

- Monastics are human. So when examples arise of monastics taking part in "outside" world politics, protest, demonstrations and teaching against resistance, against injustice by a government, yes that too is monastic. If well done, it too is a form of prayer. Being human, and not always perfected in monasticism and prayer, things sometimes get out of hand when monastics take to the street.

So now that we have encountered some experts in prayer ...

Shouldn't we ask them our important questions?

Why pray? What do you see as the benefits of prayer? And to reveal a piece of the answer, what is the benefit to the monastic? And closing in on the theme of this site, what is the benefit to the world? Is prayer effective? How do we know? How do we see and notice the benefit? And to attain these benefits, is there a tool, a method, a means that goes beyond prayer?

Perhaps here we will find, that that too, is prayer.

Visit a community of monastics.

There are many reasons to do this. In those where this is possible, you will probably, and perhaps suddenly, feel very welcomed.

One reason to do this, is to investigate for yourself, to see if, perhaps as you leave, a certain sensation or assuredness, leaves with you.

That assurance feels something like this,... a question, a hunch, something to ponder on the way home:

Can these monastic practices make us aware of, and effectively bring us to a "Butterfly Effect" where no prayer, no message, no Challenge, can be practiced without having an effect? Perhaps a desired effect for an action or need. A request that became an intention within the practice of the monastic community. Perhaps an effect that keeps our world spinning correctly on its axis?

A practice where no good word is too small, to contribute to the Beauty that is Compassion and Peace.

Hey. That's The Challenge.

can these monastic practices make us aware and effectively bring us to a "Butterfly Effect" where no prayer, no message, no Challenge, can be practiced without having an effect to keep our world spinning correctly on its axis? Where no good word is too small, to contribute to the Beauty that is Compassion and Peace